Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 56, No.4 - Winter 2010

Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavėnas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 56, No.4 - Winter 2010 Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavėnas |

Pranas Lapė: The Journey of an Artist

AUŠRA MARIJA SLUCKAITĖ-JARUŠIENĖ

AUŠRA MARIJA SLUCKAITĖ-JARUŠIENĖ is an essayist and editor who, together with her husband Jonas Jurašas, emigrated to the West in 1974 and was a correspondent and senior editor for Radio Free Europe in New York and later in Munich. She has published four books and numerous articles and reviews.

www.lass.lt

|

It is not an easy task to write about Pranas Lapė (1921-2010). Like a mythical fish in the Atlantic or Baltic waters, he eludes the net. Like the mysterious whiskered catfish, who skulks alone for long periods of time in the river’s deep bends, he is difficult to catch, but when unexpectedly hooked, he may elicit a shout of surprise: oh, what a prize! Pranas Lapė – painter, graphic artist, book illustrator, visual arts educator, gourmand and a fine culinarian! Visual artist – philosopher. He did not like the word “artist”, because it confuses the whole (art) with its part (visual arts). Regardless of where he lived, his art was solitary, not bound to society, not connected to art movements, not a few of which whizzed by during his not so brief life. An erudite and articulate conversationalist, he was at the same time an introvert, withdrawn into himself. Gifted with a sense of humor, he was sarcastic, but also easily offended. He lived in several cultures and always remained a stubborn žemaitis. “I never departed from Lithuania,” he told me, when I met him in Vilnius, after he had returned from fifty years of living abroad, first in Sweden, later in the U.S.

I met Pranas in the late 1970s in the small town of Chamberlaine, in the state of Maine. He lived on the Atlantic Coast, not unlike a monk of the Trappist order, feeding on vegetables he grew, on fish he caught, on mushrooms he picked. And he painted. At that time, he had already left his work as a teacher in order to devote himself to painting and moved here from the state of Massachusetts, from Belmont Hill, where for a long time he had taught visual arts. Pranas said that he chose Maine because it reminded him of Lithuania: nature, the landscape, picturesque low-hanging clouds floating across the sky, the scent of evergreen forests. The winters here are cold, the summers relatively cool. He was attracted by the colors of the north: black, white, and blue – like Estonia’s flag, he would joke. Perhaps it had something to do with Pranas being born in the port city of Klaipėda – he was drawn to the sea, to expansive waters. He lived in a seemingly modest but spacious box-shaped house, reminiscent of a New England barn, a large part of which was occupied by his studio. He painted large and somewhat menacing canvases in black and white. Many unfinished works were propped up against the walls.

Pranas was a hospitable host. He amazed his guests with the gourmet dishes he prepared, especially his freshly caught fish, which he prepared not sparing the butter: “Fish like to swim. It swam in water, now it must swim in butter,” he would say. With the fish he served green beans from his garden and, of course, wine, whose characteristics he would describe in lengthy discourse, adding one or two anecdotes about the art of savouring wine. The dinners were late and prolonged because Pranas liked to discuss various topics, sooner or later digressing into the broad field of art history. With delight and with humor he spun complicated webs of ideas, at times sarcastically testing his guest’s ability to view things with a critical eye. Often he broke out into delicious, contagious laughter.

Among his American friends and neighbors, Pranas was renowned as an extraordinary conversationalist. Andy Rooney, essayist and well-known commentator of the CBS television program 60 Minutes, wrote about Lapė in a piece called “The Lost Art of Conversation”: “Pranas Lapė is one of the best conversationalists that I know. He has original ideas, serious thoughts and usually emphasizes them with such unexpected twists that he forces everyone to laugh.” (Ludington Daily News, 1983). Rooney also described the painter’s “monastic existence” on the coast of Maine, his ability to live modestly on what he grows in his garden and catches in the sea, his friendship with his French summer neighbor Roget Fessaguet, one of America’s finest chefs and the owner of the New York restaurant La Caravelle. Rooney does not fail to mention Pranas’s large abstract canvases in which, according to Rooney, there are “undoubtedly no fewer interesting ideas than there are in his passionate discourses, even though not everyone might understand his art.”

Pranas Lapė lived in Chamberlaine for some two decades, a period of time that was very important in his creative journey. The cold colors, menacing coastal cliffs, and huge dark forests affected his imagination, his color palette and his technique of painting. He spoke about that a lot during our final conversation in Vilnius last autumn:

“When I lived in Maine, my principal color was black: severe cliffs by the ocean, all of the surroundings I do not see colors, they appear when the evening sun falls on the cliffs. Objects have no color. I can give color to them. The color black is interesting. You can paint anything you want in the color black. In the past you were required to first paint in black and white and then to apply colors. I recall the Swedish painter Anders Zorn. With a broad brush he painted landscapes, nude women. Once when I lived in Sweden, we were traveling around Lake Siljan and found a summer home that was round and that grew narrower toward the top, like the Swedes were building then. It was Zorn’s summer studio. When I saw his easel I was surprised that the palette had only four colors or so: ochre or red, black, blue, white. There hung a picture – half was without color, the other half with color. Why? This stuck with me…”

Remembering his creative period in Maine, Pranas said that then he was especially interested in forms – decorative, dramatic masses of cliffs. He painted in black and white, seeking to achieve vibration and depth:

“At the Whitney Museum I saw Franz Kline’s impressive works, but the color black did not vibrate, it was flat… While in Rothko’s works the color black was full of atmosphere, not flat, with brush strokes…”

Pranas discovered his own technique – to paint with liquified paint, diluted with turpentine and applied on the canvas with a scrap of cloth:

“When you remove that rag, you get a gray color, texture. You need to work very quickly, the liquified paint evaporates, almost driving you out of the house. I tried painting outside. The paint is toxic, I needed a gas mask. I got poisoned. Developed an allergy to turpentine. Later on they started to make it odorless, but just the sight of turpentine made me break out immediately into a rash and begin to itch…”

The stained glass designer Albinas Elskus, who had a studio nearby, advised Lapė to use kerosene, but that was even worse. Pranas subsequently wanted to return to colorless painting. He found the process itself interesting: the pulsating colors, the dramatic and decorative effect. But he couldn’t find the large space he needed to paint several pictures at once, to experiment with brush strokes, while the paint was still wet. Then his painting was invaded by the colors of Maine: blue, like the boundless ocean, like the tall sky. Green, like the dark woods. White, like the balls of clouds… Nature always had an effect on Pranas. But it was not just color. What was important, according to the painter, was the actual technique of painting, the energy of the action, which is obvious in the canvases of abstract expressionism. Lapė was charmed by the school of New York abstract expressionists and this enchantment did not subside. “Abstract expressionists are very interesting painters: Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko…” he spoke during our last conversation.

Returning to his past, Pranas at that time also recalled the beginnings of his “dabblings at painting.”

“I liked to paint pictures when I was in high school. I spent my summers with my grandparents in Vieviržėnai, not far from Rietavas. My grandfather, born in 1854, was not very tall. He dealt with kids as if they were his equals. He would warn me that knowledge is a bad thing, that it’s harmful. But no harm came of it… I remember he would ask me when it rained: ‘Are there more round rocks or oblong rocks?’ And while I deliberated in puzzlement, he would answer: ‘Wet ones, you dummy.’ Once he asked me: ‘You paint pictures, can you paint me a picture of Jesus Christ?’ He wanted one, so I painted it for him. With colors, oil paints. I did not critique my own work. I thought that everything I painted was good. The old man took it to the pastor to get it blessed, and the pastor said: ‘It’s a bad picture’ and wouldn’t bless it. See what an art critic he was. All painters should present their work to their pastors for criticism,” laughed Pranas.

He recalled the impression left on him by his high school art teacher, the painter Vytautas Kairiūkštis, who in 1939 took his students to the French modernist show in Kaunas. Kairiūkštis held Bonnard in very high regard, while Pranas, then and later, was most impressed by Cézanne, because there is mystery in his pictures.

“Cézanne’s painting is intellect, it is planned. It is not spontaneous. You can see that everything is thought out beforehand, everything is based on logic. But the mystery remains nonetheless. That is amazing.”

Pranas Lapė’s creative journey, which began with his high school “paint dabblings,” took him to the Kaunas Art School, where at first he studied ceramics and later became interested in drawing and painting. As the second Soviet occupation approached, he withdrew to the West. In 1945, traveling a complicated route, he reached Sweden and continued his studies in Stockholm, at the private school of Anders Beckman. There later on he himself became an instructor of drawing. He created several wall murals for public buildings, illustrated books, designed several major events. The Swedish chapter of his journey was not a long one, and creatively it was not especially significant. Nonetheless, it was interesting to get to know a completely different, a Scandinavian, culture. After five years, Pranas emigrated to the United States. He lived in New York City and later on Long Island.

He was contracted to draw illustrations for well-known New York publishers, such as Doubleday, Random House, Scribners, and so on: “I do them, submit them on Friday and then I’m free, I can paint… My paintings then were in a small format. More like experiments. At that time, my influence was Cézanne, later Claude Monet. He did away with the horizon, which delimits the sky (that’s how I see his Water Lilies at the Museum of Modern Art in New York). Monet painted gardens, flowers, melding the colors into one fabric… Here you see the transition to abstraction. Abstract expressionism brought attention to the stroke of the paintbrush, liberated it from the image… I was interested, I delved deeper… That was my time of searching. I began painting seriously only when I settled in Maine,” recounted Pranas.

While he lived in New York and while he taught art at the Rowayton School in Connecticut and the Belmont Hill School in Massachusetts, Pranas designed more than two hundred book covers for U.S. publishers and illustrated books by Lithuanian authors: Antanas Baranauskas’s Anykščių šilelis, Maironis’s Baladės, Juozas Lukšas-Daumantas’s Partizanai and others. Living in Maine, he created noteworthy illustrations for Algimantas Mackus’s Augintinių žemė and Antanas Gustaitis’s Pakelėje į pažadėtąją žemę. But later he concentrated only on his passion for painting.

When Lithuania reestablished its independence, Pranas returned to Lithuania, from which, as he himself would say, “he had never departed.” He would return intermittently – at first he summered in Maine, where he still had his studio, and he would spend winters in Vilnius. He felt as if he had returned home and his stays there grew longer and longer. Some seven years ago, Pranas finally moved permanently to Tiltas Street, where he also set up a small studio. His painted works grew in number and no longer fit in the studio. Unframed, unsigned, in rolled up canvases, they seemingly waited for the day when they would go public.

The art community was reserved in its welcome. There was only one organized show of his paintings at the National Museum. Galleries apparently were not interested in him, only rarely did his name flit across the pages of the cultural press, his colleagues also did not pay much attention to him. To the outside observer, it was as if he did not belong to the surrounding art world, as if he had not returned at all. One might say that he had remained in the “land of foster children” in the words of poet A. Mackus. Pranas himself never complained about it (at least not to me). He was interested in everything going on in Lithuania, vigorously reacted to it all, enjoyed commenting on political and cultural current affairs with his perfectly aimed humor and light sarcasm. The lack of interest in him apparently did not bother him. As long as he could paint, his life was complete.

Pranas spent most of his time at the easel. He painted with enthusiasm, interrupted by no one, taking pleasure in the silence surrounding him. Bold paint strokes, lush deep colors, a mysterious glow from within – it was all there in those paintings. I recall his canvases of a deep blue color scheme as if flooded by the northern lights, the dramatic bursts of ochre against a dark background, the scale of green tones in the dyptich. His palette grew lighter. Now came the time for color and light. A vivid flash preceded the approaching blanket of complete darkness.

Pranas’s eyesight began to fail suddenly. Operations did not help. On the contrary. Colors grew dim, objects and people turned into silhouettes. The day came when Pranas could no longer paint at all. His impairment painfully gnawed away at him and he began to sink into depression. A year later he had lost his sight completely. He was cloaked in solitude and darkness. Blindness is a misfortune for anyone, but for a painter it is especially tragic. A sightless poet or musician can still create and hear what he had created earlier. The blind bard has been romanticized since antiquity as a wise man, a prophet. A blind painter loses not only the ability to create but, in a certain sense, also loses all the works he has ever created because he will never be able to see them again, or return to them to make a selection. Pranas would say that he saw colors and paintings in his dreams. He lived in his memories.

I visited Pranas last October. I brought a bottle of the red wine he liked. He was happy with every one of his rare visitors. And he was happy to have me visit him. He looked thin, somewhat frail, but, as always, his mind was sharp and his phenomenal memory had not grown weak. I took his hot hand, led him to the sofa and handed him the glass of wine. He smiled and it seemed as if he gave me an intent look through his dark sunglasses. I had been meaning to write about Pranas for a long time, but I didn’t dare mention it to him – he liked to poke sarcastic fun at anyone who spoke out about art and expressed an opinion. Pranas had indisputable views about artistic phenomena. And whenever I tried to shift the conversation toward him as an individual, he quickly burst into a long monologue about some completely tangential subject that popped into his head. Regarding his personal life, Pranas would talk willingly only about the odyssey of his journey to the West, and so minutely and in such detail that before he had even reached Sweden, I, to my shame, had already forgotten the beginning of the story. Anything that was more intimate about him was kept under lock and key. He very rarely talked about his works.

But this time it was different. He spoke gently, with some melancholy, digressing widely into the sources of art, its connection with religion, the history of painting, its shifts and breaks, constantly throwing out, like a piece of glitter, a memorable phrase or aphorism, citing Picasso or himself. “Painting is mute poetry, and poetry is painting that speaks,” he said, plunging into ruminations about Plato and the debate on mimesis. Afterwards, in a rueful tone, he added: “I should have studied philosophy.”

That evening he was easily drawn into a discussion about his own creative work:

“You take a canvas. It’s a beautiful, exciting space, but it’s only space. A white canvas, nothing more. You can change it by placing one dot on it. You can change it even more by making a brush stroke. In that space you can do whatever you want. Sometimes, when you begin to paint, you have an idea. When you dive into abstraction, it’s better not to have an idea. The first dab of paint on an empty canvas represents the beginning and then the journey starts. You don’t know where it will take you. Columbus was the first real artist, because he sailed for India, but instead discovered America. True creation is a journey.“ Pranas stressed the word “journey” and sighed. He raised the glass to his lips. He drank from it.

“A good wine, subtle. That’s what I prefer now,” he rated it after tasting it. “Women usually don’t know wines… What kind is this?”

“I’d rather we returned to the canvases, to your journey,” I replied, stealing glances at his dark glasses and the darkening sky outside the window.

“I wanted the entire process of painting to be like a journey to the unknown. At a particular moment you come upon something and then you continue… If you sail long enough you’ll eventually come back. If you travel a long time, you’ll come to yourself. Sometimes you need to stop, when you feel that you have reached your destination. You need to know when to stop. The creative impulse is one thing, while thinking is another. Do you decide or do you sense when it’s time to stop? Picasso said: I paint and there comes the moment when I don’t know what I should do next. I stop. A month or two later I look again and the work is done, completed. When you work, especially when you work quickly, you reach a point when you must stop. Put it aside. But I sometimes would start to rework, to repaint. If you keep going back to one work, you torture it and yourself. Whenever I worked I would get so immersed, so drawn into it, that I would make myself ill. I’d lose interest in eating and everything else. If you would only stop and later on take a look, you would see that the picture had been finished long ago… In painting you can achieve direct expression. Petras Kiaulėnas liked to talk about a manuscript – painting is like a manuscript, maybe a diary? An example of direct expression is my Žalia drobė (Green canvas) in two parts… Painting must have mystery… Painting is suspended music…”

Outside the window it was pitch

black. I closed my notebook.

I didn’t dare to turn the light on in the room.

“It’s dark, Pranas. I have to go,” I

reluctantly interrupted

him.

“It’s always dark for me,” he answered

irritably.

“What was the last thing you were working on, when you

stopped painting?”

“I was not working on just one picture. I left several of

them unfinished. I couldn’t complete them… I left

empty canvases…”

I rose to leave. I could see that

Pranas wanted to accompany

me to the door. I took him by the arm and we walked feeling

our way in the dark, as if we both were sightless.

“So you’re leaving again?” he asked and

unexpectedly

added:

“In America I was a Lithuanian. Living in Lithuania I felt

like an American. It’s that I see life differently.

It’s hard to understand

a lot of things here, many of the social and government

issues, the tax system, demands for state support… I listen

to the radio and so much of it seems absurd. But why talk

about that… I’m glad that you came. Very glad. You

brought

me light.”

I hugged Pranas, and said that

I’d see him in the spring.

He gripped my hands with his hot palms.

“Promise that you’ll come…

There’s so much that still

needs to be said. Promise,” he asked.

“I promise.”

I will not be able to keep my promise. Pranas Lapė’s journey ended January 13, 2010, two days after his eighty-ninth birthday.

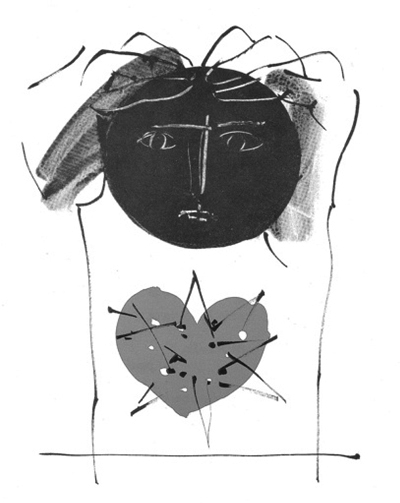

Illustration from Antanas Baranauskas’s, "Anykščių šilelis".

Romuva, 1961.

Illustration from Algimantas Mackus’s "Augintinių žemė".

Algimanto Mackaus knygų leidimo fondas, 1984.